Mechanical resonance

Mechanical resonance is the tendency of a mechanical system to absorb more energy when the frequency of its oscillations matches the system's natural frequency of vibration (its resonance frequency or resonant frequency) than it does at other frequencies. It may cause violent swaying motions and even catastrophic failure in improperly constructed structures including bridges, buildings and airplanes—a phenomenon known as resonance disaster.

Avoiding resonance disasters is a major concern in every building, tower and bridge construction project. As a countermeasure, shock mounts can be installed to absorb resonant frequencies and thus dissipate the absorbed energy. The Taipei 101 building relies on a 660-ton pendulum — a tuned mass damper — to cancel resonance. Furthermore, the structure is designed to resonate at a frequency which does not typically occur. Buildings in seismic zones are often constructed to take into account the oscillating frequencies of expected ground motion. In addition, engineers designing objects having engines must ensure that the mechanical resonant frequencies of the component parts do not match driving vibrational frequencies of the motors or other strongly oscillating parts.

Many resonant objects have more than one resonance frequency, particularly at harmonics (multiples) of the strongest resonance. It will vibrate easily at those frequencies, and less so at other frequencies. Many clocks keep time by mechanical resonance in a balance wheel, pendulum, or quartz crystal.

Contents |

Description

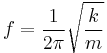

The natural frequency of a simple mechanical system consisting of a weight suspended by a spring is:

where m is the mass and k is the spring constant.

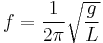

A swing set is a simple example of a resonant system with which most people have practical experience. It is a form of pendulum. If the system is excited (pushed) with a period between pushes equal to the inverse of the pendulum's natural frequency, the swing will swing higher and higher, but if excited at a different frequency, it will be difficult to move. The resonance frequency of a pendulum, the only frequency at which it will vibrate, is given approximately, for small displacements, by the equation[1]:

where g is the acceleration due to gravity (about 9.8 m/s2 near the surface of Earth), and L is the length from the pivot point to the center of mass.(An elliptic integral yields a description for any displacement). Note that, in this approximation, the frequency does not depend on mass.

Mechanical resonators work by transferring energy repeatedly from kinetic to potential form and back again. In the pendulum, for example, all the energy is stored as gravitational energy (a form of potential energy) when the bob is instantaneously motionless at the top of its swing. This energy is proportional to both the mass of the bob and its height above the lowest point. As the bob descends and picks up speed, its potential energy is gradually converted to kinetic energy (energy of movement), which is proportional to the bob's mass and to the square of its speed. When the bob is at the bottom of its travel, it has maximum kinetic energy and minimum potential energy. The same process then happens in reverse as the bob climbs towards the top of its swing.

Some resonant objects have more than one resonance frequency, particularly at harmonics (multiples) of the strongest resonance. It will vibrate easily at those frequencies, and less so at other frequencies. It will "pick out" its resonance frequency from a complex excitation, such as an impulse or a wideband noise excitation. In effect, it is filtering out all frequencies other than its resonance. In the example above, the swing cannot easily be excited by harmonic frequencies, but can be excited by subharmonics.

Examples

Various examples of mechanical resonance include:

- musical instruments (acoustic resonance).

- Most clocks keep time by mechanical resonance in a balance wheel, pendulum, or quartz crystal.

- tidal resonance of the Bay of Fundy.

- Orbital resonance as in some moons of the solar system's gas giants.

- The resonance of the basilar membrane in the ear.

- Making a child's swing swing higher by pushing it at each swing.

- A wineglass breaking when someone sings a loud note at exactly the right pitch.

Resonance may cause violent swaying motions in improperly constructed structures, such as bridges and buildings. The London Millennium Footbridge (nicknamed the Wobbly Bridge) exhibited this problem. A faulty bridge can even be destroyed by its resonance (see "Angers Bridge"; that is why soldiers are trained not to march in lockstep across a bridge, although it is suspected to be a myth, see e.g., MythBusters' 'Breakstep Bridge'. Mechanical systems store potential energy in different forms. For example, a spring/mass system stores energy as tension in the spring, which is ultimately stored as the energy of bonds between atoms.

Resonance disaster

In mechanics and construction a resonance disaster describes the destruction of a building or a technical mechanism by induced vibrations at a system's resonance frequency, which causes it to oscillate. Periodic excitation optimally transfers to the system the energy of the vibration and stores it there. Because of this repeated storage and additional energy input the system swings ever more strongly, until its load limit is exceeded.

Failure of the original Tacoma Narrows Bridge

The dramatic, rhythmic twisting that resulted in the 1940 collapse of "Galloping Gertie", the original Tacoma Narrows Bridge, is sometimes characterized in physics textbooks as a classic example of resonance; however, this description is misleading. The catastrophic vibrations that destroyed the bridge were not due to simple mechanical resonance, but to a more complicated oscillation caused by interactions between the bridge and the winds passing through its structure — a phenomenon known as aeroelastic flutter. Robert H. Scanlan, father of the field of bridge aerodynamics, wrote an article about this misunderstanding.[2]

Other Examples

- Collapse of Broughton Suspension Bridge (due to soldiers walking in step)

- Collapse of Angers Bridge

- Collapse of Königs Wusterhausen Central Tower

- Resonance of the Millenium Bridge

- Evacuation of the 39-story TechnoMart commercial-residential high-rise in Korea (due to a Tae Bo class, 2011)

Applications

Various method of inducing mechanical resonance in a medium exist. Mechanical waves can be generated in a medium by subjecting an electromechanical element to an alternating electric field having a frequency which induces mechanical resonance and is below any electrical resonance frequency.[3] Such devices can apply mechanical energy from an external source to an element to mechanically stress the element or apply mechanical energy produced by the element to an external load.

The United States Patent Office classifies devices that tests mechanical resonance under subclass 579, resonance, frequency, or amplitude study, of Class 73, Measuring and testing. This subclass is itself indented under subclass 570, Vibration.[4] Such devices test an article or mechanism by subjecting it to a vibratory force for determining qualities, characteristics, or conditions thereof, or sensing, studying or making analysis of the vibrations otherwise generated in or existing in the article or mechanism. Devices include methods to cause vibrations at a natural mechanical resonance and measure the frequency and/or amplitude the resonance made. Various devices study the amplitude response over a frequency range is made. This includes nodal points, wave lengths, and standing wave characteristics measured under predetermined vibration conditions.

Earthquake machine

Nikola Tesla established a laboratory at 46 E Houston Street in New York. There, at one point while experimenting with mechanical oscillators, he allegedly generated a resonance of several buildings causing complaints to the police. As the speed grew it is said that the machine oscillated at the resonance frequency of his own building and, belatedly realizing the danger, he was forced to apply a sledge hammer to terminate the experiment, just as the police arrived.[5] The Mythbusters television program made a small machine based on the same principle, but driven by electricity rather than steam, to test the claimed earthquake effect; it produced vibrations in a large structure that could be felt hundreds of feet away, but no significant shaking, and they judged the effect to be a busted myth.

See also

- Resonator

- Reed switch

- Transducer

- Electrical resonance

- Laser applications

- Resonance disaster

- Dunkerley's Method

- String resonance

Notes

- ^ Mechanical resonance

- ^ K. Billah and R. Scanlan (1991), Resonance, Tacoma Narrows Bridge Failure, and Undergraduate Physics Textbooks, American Journal of Physics, 59(2), 118--124 (PDF)

- ^ Allensworth, et al., United States Patent 4,524,295. June 18, 1985

- ^ USPTO, Class 73, Measuring and testing

- ^ O'Neill, "Prodigal Genius" pp162-164

Further reading

- S Spinner, WE Tefft, A method for determining mechanical resonance frequencies and for calculating elastic moduli from these frequencies. American Society for testing and materials.

- CC Jones, A mechanical resonance apparatus for undergraduate laboratories. American Journal of Physics, 1995.

Patents

- U.S. Patent 1,414,077 Method and apparatus for inspecting materials

- U.S. Patent 1,517,911 Apparatus for testing textiles

- U.S. Patent 1,598,141 Apparatus for testing textiles and like materials

- U.S. Patent 1,930,267 Testing and adjusting device

- U.S. Patent 1,990,085 Method and apparatus for testing materials

- U.S. Patent 2,352,880 Article testing machine

- U.S. Patent 2,539,954 Apparatus for determining the behavior of suspended cables

- U.S. Patent 2,729,972 Mechanical resonance detection systems

- U.S. Patent 2,918,589 Vibrating-blade relays with electro-mechanical resonance

- U.S. Patent 2,948,861 Quantum mechanical resonance devices

- U.S. Patent 3,044,290 Mechanical resonance indicator

- U.S. Patent 3,141,100 Piezoelectric resonance device

- U.S. Patent 3,990,039 Tuned ground motion detector utilizing principles of mechanical resonance

- U.S. Patent 4,524,295 Apparatus and method for generating mechanical waves

- U.S. Patent 4,958,113 Method of controlling mechanical resonance hand

- U.S. Patent 7,027,897 Apparatus and method for suppressing mechanical resonance in a mass transit vehicle

External links

- Mechanical resonance : study the resonance behavior of a mechanical oscillator; physics.rutgers.edu